- Date of visit: 11.11.2025

- Post office visited: General post office in Yangon, Nyaung U post office

- Cost of sending postcard: 1,000 kyat (about 0.40 eur)

- Postcards available at: General post office Yangon, gift sellers on front of Ananda Temple

- Delivery time: quickest were the UK and Japan — 14 days

A Brief Look at Myanmar’s Postal History

Myanmar’s postal system traces its roots back to the messenger networks of the Burmese kingdoms, later reorganized under British rule. From the late 19th century until 1937, Burma was administered as part of British India and used Indian stamps with local cancellations. Independent Burmese stamps appeared in 1937, and a national postal service was established after independence in 1948.

A few unusual turns shaped the system that followed: Burmese stamps issued during the Japanese occupation in World War II, then decades of military rule and political isolation that restricted international mail links and slowed modernization. Yet despite everything, Myanmar remained a member of the Universal Postal Union, and its post offices kept operating even in remote corners of the country.

Our trip to Myanmar

When the military seized power in February 2021, overthrowing the elected government, Myanmar suddenly felt like a place I might never see. Protests, crackdowns, collapsing institutions — the country slipped from my “one day I’ll go” list into a cloud of uncertainty. For a long time, visiting felt impossible.

And yet here we were, reading threads in backpacker forums. Eventually, Andry and I ended up deciding to go. Yes, despite the fact that several governments still officially advise not travelling there.

We promised ourselves to be cautious: stay at the hotel if needed, use taxis only for essential errands like getting to the post office, and — if things felt safe enough — try to see the Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar’s most sacred Buddhist site.

But when we landed at Yangon Airport on the evening of 10 November, it quickly became clear that our fears had been exaggerated. After a night at the hotel and a morning run in the nearby park — surprisingly lively with groups doing morning exercises — we headed to the main post office. We took a Grab (the local Uber), not for safety but simply because it was far.

The Yangon General post office building itself was beautiful — a solid 1908 structure full of character. The stamp counter was right by the entrance. Their online store lists a huge variety of stamps, but the actual choice on-site was… minimal. One design per denomination.

Behind the counter were a man and a woman, ready to sell us stamps — but only that one type. After several polite attempts to ask whether they had anything else, and even showing them their own website, we received the same gentle “no” every single time.

Eventually, one of them directed us upstairs, where plenty of staff were working, and about five of them rushed over to help — which momentarily gave us hope. But the selection didn’t improve at all. They did show us a stamp book. It was lovely. Unfortunately, none of the stamps in it could actually be bought on-site.

According to our research, sending a postcard should cost 1,000 kyat — and that turned out to be true. But reliable information about which countries they could actually send to was almost impossible to find. There were parcel lists, yes, but past experience has taught us that those aren’t always accurate.

So this became our next question.

The first confident answer was: “All countries except the USA.” Great, we thought — but also unbelievable. So we decided to test the limits of their optimism and named a few “unlikely” destinations such as Chad and Afghanistan.

That’s when we were redirected from one counter to another, on different floors, and eventually ended up with a partially printed list (only countries up to the letter M) and a handful of additional destinations scribbled on the back. It turned out there were more countries they couldn’t send to — including our own Estonia.

We bought the stamps they did have and the few postcards available at the same counter — all 24 of them — and instead of going back to the hotel to start writing, we decided to head out and explore the city.

Shwedagon Pagoda was an obvious stop — the kind of place that glows even before you reach it, a vast golden complex dominating the skyline.

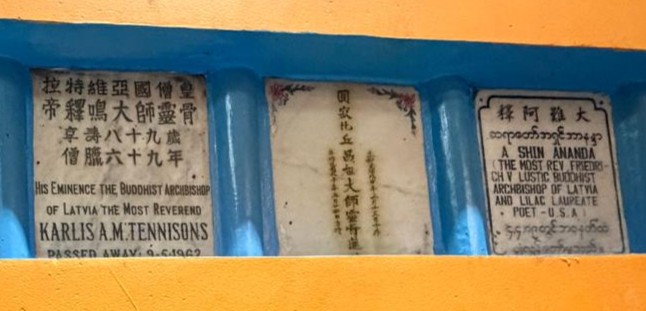

‘But we had another, more unusual reason to visit: Vahindra — born in Estonia in 1883 (Karl Tõnisson / Karlis Tennisons) — and his disciple Friedrich Voldemar Lustig. Both had colourful and contradictory lives, and both spent their final years in Yangon, where they passed away and are buried in a nearby Buddhist temple complex. Both were among the earliest Western-born Buddhist monks connected to Burma.

Since they were born in Estonia — and their story is truly remarkable — I simply wanted to mention these two unbelievable men in my blog as well.

By the next evening, I had made a new plan.

I decided to take the twelve-hour night bus to Bagan — not for the post office, but because where else on earth do more than 2,200 ancient pagodas rise from a single plain? Most of them date back to the 11th–13th centuries, the last survivors of the 10,000 temples that once covered the valley — a UNESCO World Heritage wonder I simply could not miss.

So I bought a ticket and boarded a fully booked bus. My seatmate, a man from Bagan, didn’t speak English but enthusiastically offered to guide me — though in the end, I politely declined.

A night of almost no sleep was instantly forgotten the moment I saw the landscape of temples stretching in every direction.

I dropped my backpack at the hotel and walked to the nearby Ananda Temple. As I was leaving, a tuk-tuk driver offered a day tour around the pagodas — I said yes, and it turned out to be a great choice. He had worked as a licensed guide before COVID, back when more tourists came. Driving between pagodas, visiting small bamboo lacquer workshop (Mya Thit Sar, Myin Ka Pa, Bagan) and sugarcane producers felt surreal.

Yes, I know — this blog is supposed to be about post offices, not pagodas or…

But the trip is so fresh and overwhelming that staying strictly on topic felt impossible.

So, to get back on track: before the sunset ride, we made a quick stop at the post office.

The post office in Nyaung U (near Bagan) looked surprisingly impressive — a solid, eye-catching building that also functions as the local telecommunications center. Inside, two smiling women greeted me with a warm “Mingalaba,” Myanmar’s equivalent of “hello,” but everything after that took place through Google Translate — and it worked flawlessly.

I stamped four postcards I had prepared in advance and continued the tour with my tuk-tuk driver.

Sunset in Bagan was indescribably powerful. Even after nearly 24 hours without real sleep, it was absolutely worth it.

The next day was no less full of impressions, and by evening it was already time for me to begin the twelve-hour journey back to Yangon.

Meanwhile, Andry revisited the main post office in Yangon— this time armed with a printed list of countries. The clerk marked reachable destinations by hand and even stamped the sheet for good measure. Andry sent far more postcards than I did. Since Estonia wasn’t on the list, he ended up sending our cards through two different routes: via Germany and via Finland. Fingers crossed they arrive.

Somehow Myanmar got under my skin more deeply than I expected. Beyond postcards and stamps, conversations with people — despite the language barrier — touched on everything: education (free, but with too few teachers), beggars lining the roads from Bagan to Mount Popa during the holidays, ongoing fighting in several regions, stories about scam-centres where foreign workers are held against their will, daily survival, and even marriages.

And when I asked about the country’s name and the upcoming elections, the answers were remarkably consistent. Almost everyone preferred “Myanmar” over “Burma,” saying it reflects all the peoples living here — even though there was never a public referendum on the name change. And none of them planned to vote; the elections, they said, were only for show, meant to impress the outside world, and wouldn’t change anything.

My “elephant question” also got its answer from a very knowledgeable Yangon taxi driver. (From each country, I collect a local version of an Estonian cultural elephant joke.) He told me that centuries ago, the birth of a white elephant was considered a royal omen — proof that the king’s rule was just. A couple of years ago, the junta announced that a white elephant had been born, supposedly proving their legitimacy.

The taxi driver and his friends, however, are convinced that the elephant isn’t truly white at all — just painted.

But it was time to leave. Our journey continued on the national airline, MAI, dozens of postcards sent — and a small piece of this country firmly lodged in my heart.

For now, this story ends here — a new post will follow in two weeks.

If you’d like to read future entries from this post office diary, you can subscribe here.

What a beautiful story and adventure! You are an inspiration!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I received my postcard from Myanmar via Laos today (mailed to the USA)! I have enjoyed reading over these entries and hearing about the adventures you and my card took! Thank you so much for sharing these parts of the world with me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m very happy to hear that you enjoyed it and that the postcard finally reached you! Thank you for your kind words! Some postcards from Myanmar and Laos are still on their way…

LikeLiked by 1 person

keep on visiting foreign post offices!

LikeLiked by 1 person