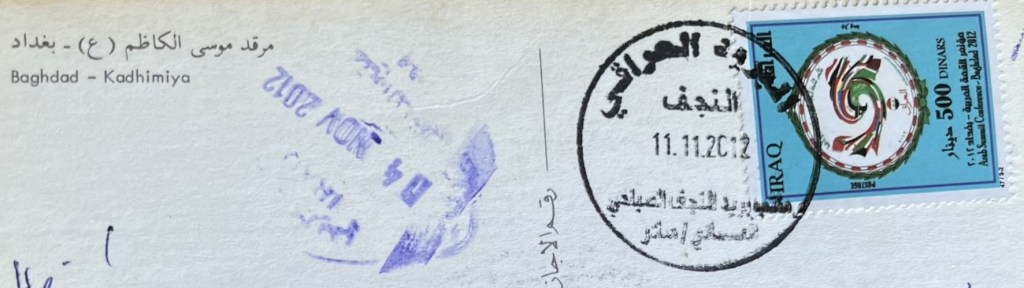

- Visit date: 11 November 2012

- The visited post office: A Post Office in Baghdad

- Cost of sending mail: 500 dinars

- Postcard Delivery Times: fastest-12 days to Germany and to Netherlands

A bit of postal history from Iraq

Although Iraq as a modern state is just over a century old, the region has been sending messages for thousands of years. In ancient Mesopotamia, people used clay tablets sealed in addressed envelopes — possibly the world’s earliest form of postal service.

Fast forward a few millennia: by the 1860s, Ottoman post offices were active in Baghdad, Basra and Mosul. After World War I, the British took over and started issuing stamps marked “Iraq” from 1923 onward. In 1932, with full independence, the country introduced its own currency and royal-themed stamps.

Since then, Iraq’s stamps have reflected its turbulent history — from monarchy to republic, from Saddam-era portraits to modern commemorative. Even today, despite challenges, the postal system keeps going.

Our Journey into Iraq – November 2012

When we arrived in Iraq in November 2012, the official message from the local travel agency was clear: the country was peaceful, stable, and ready to welcome tourists. Technically, they weren’t wrong — there was no war, and no active fighting in the south. Our hosts reassured us there was no danger.

But especially in hindsight, things were more complicated.

In the months leading up to our trip, Iraq’s Sunni vice president, Tariq al-Hashemi, had been sentenced to death in absentia — a move that deepened sectarian mistrust. Bombings were once again frequent in Baghdad and Shiite-majority areas, with dozens killed just weeks before our arrival. The U.S. military had withdrawn the previous year, and the Iraqi government was struggling to hold the country together.

And this was exactly the kind of country we arrived in — a group of 13 Estonians.

Was I nervous? Absolutely. But I didn’t want to back out either — especially since our local travel agency kept insisting that everything was perfectly peaceful.

To our surprise, we were met at the airport not only by our two local guides, but also by two trucks, each carrying six-seven armed men and a machine gun. And a small minibus for us.

The official explanation? “It’s so peaceful these days that the security forces are bored — so they’re coming along.”

For the first few nights, we stayed at the Baghdad Hotel. Day one included a city tour.

Traffic in Baghdad is chaotic even on a good day, and the endless checkpoints made it even slower. We walked around the city, visited a market, museums and mosques. If I or someone else paused too long to look at something, a bodyguard with a gun would gently gesture for us to stay close to the group. It didn’t feel like they were only doing this out of boredom.

In Estonia, before the trip even began, Andry had already asked if a visit to the post office could be included. He mentioned it again at the airport. The guides said they’d try to include it — but gave no clear time or promise.

Day one passed — and no post office. When we asked about it again, the response was vague. Plans changed several times that day (we later understood this was for safety reasons), and clearly, the post office was not a top priority.

So we made a plan of our own. The next morning, Andry would stay at the hotel, request a driver and car from hotel, and try to visit the post office his own. I would continue with the cultural program.

As the convoy departed the next morning, the guides quickly noticed someone was missing.

“Who’s missing? Why? Sick at the hotel?”

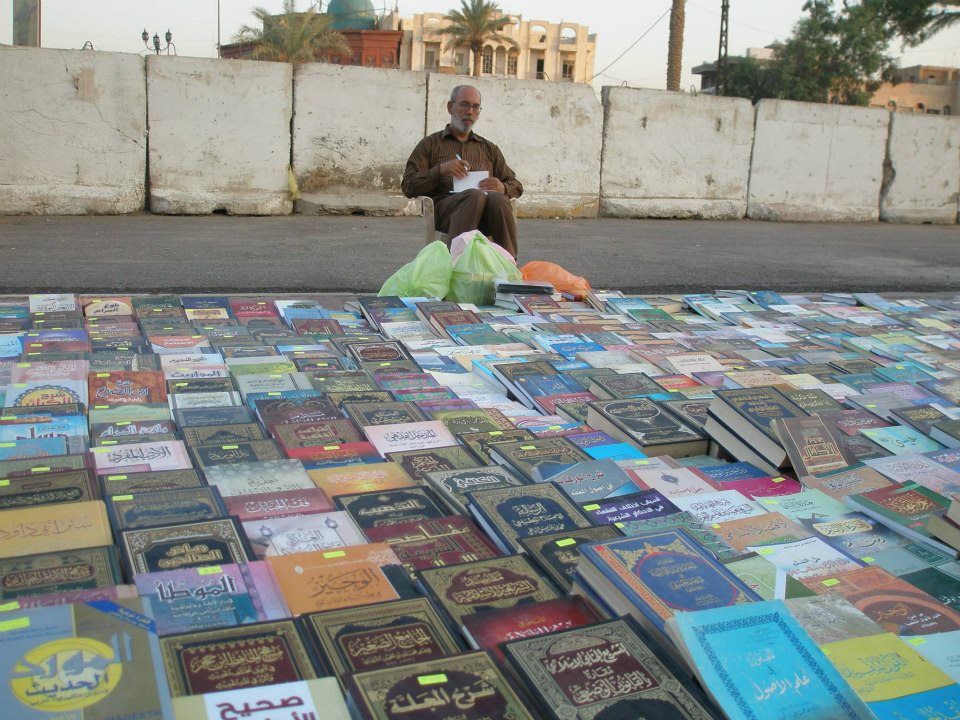

Before we could answer, they spotted Andry walking toward a bookshop — one that appeared on Google Maps, but didn’t actually exist.

The convoy stopped. The guides and armed guards ran to retrieve Andry and escorted him back to the bus.

“Yes, the country is safe,” they said, “but it’s still better if he explores the culture with us.”

More checkpoints followed — along with museums and parks. But that failed post office attempt had an unexpected positive upside. Near one market, we were taken to a street lined with bookshops, one of which even had some local postcards. A bit old and worn, but still — real postcards.

By that point, the guides had realized that Andry wasn’t about to give up on finding a way to visit a post office. So the next morning, before leaving Baghdad, they agreed to a stop. It wasn’t the main post office, but presumably one they felt was safe enough.

The postal workers were delighted to see us. Andry was guided straight to the manager’s desk and got to work — sticking stamps and getting them postmarked. After all the effort it took to get there, even group members who hadn’t planned to send postcards joined in.

We sent postcards from Iraq to many friends, but also drew random addresses through the Postcrossing system. One of Andry’s cards, unexpectedly, was headed to Israel — a complication, as Iraq doesn’t recognize the State of Israel. Our well-traveled Estonian guide, Hannes Hanso, even warned us not to mention the country by name. So we had to make a quick decision. Andry wrote the full address as required, but for the country name, he cleverly put Ireland, hoping that postal workers there would be smart enough to forward it. And they were — 205 days later, the postcard was registered in Israel.

And just like at every museum and mosque, we were offered coffee and Cola and invited — once again — to pose for a group photo.

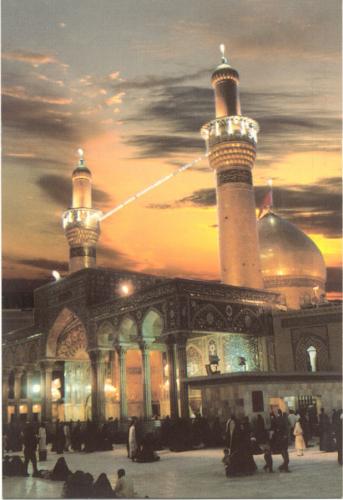

Although Iraq had officially reopened to tourism about six months earlier, we didn’t meet any other tourists from Europe or the U.S. According to our guides, however, there were many tourists from neighboring countries — most visiting for religious reasons, to see the holy cities.

After the post office, we left Baghdad.

We visited the spiral minaret of Samarra (opened just for us), walked on thousands of-years-old pottery shards in Ur and Uruk, Babylon and explored the holy cities of Karbala and An Najaf.

At each site, locals invited us to join them for group photos — even strangers on the street would stop and ask to take picture with us.

We were captivated by the ancient architecture and deep history. But for the locals, we were the real attraction.

Despite the unrest in the region, people were incredibly warm and welcoming.

More than once, someone asked us to tell people back home that Iraq is beautiful and friendly, and that tourists are welcome. This happened in the museums and in the streets but also in both Sunni and Shiite mosques.

On our last day, we took wooden boats through the river delta, to a small island near the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. There, fresh and delicious fish was grilled for us in the open air. Naturally, even for this relaxing outing, our armed guards came along — apparently, once again, out of “sheer boredom.” This time, however, they left the machine guns behind.

Our return flight from Basra was the most abrupt part of the trip. Already about twenty minutes before the scheduled departure time, we heard “Boarding completed,” and then the plane took off at a very steep angle. The German engineer sitting next to me, who worked at an oil facility in Basra, was very surprised to see tourists on board. He said he wasn’t even allowed to leave the restricted zone. Then he simply nodded and added, “That’s how it is here. No plane stays longer than necessary, and none flies lower than absolutely required.”

But just as safely as we left, so too did our postcards. The first ones arrived in the Netherlands and Germany — just 12 days later.

Violence between Sunni and Shiite factions escalated again in early 2013. Al-Qaeda in Iraq (soon to become ISIS) began gaining strength, and by March 2013, the country had its highest death toll since 2008. Shortly after our visit, Iraq once again closed to most tourists. Until around 2020, travel started to become easier again — even in central and southern Iraq.

As for Iraq’s stance toward Israel, in May 2022 the Iraqi parliament passed a law that criminalizes the normalization of relations with Israel. Violating this law can result in life imprisonment or even the death penalty.

If you’d like to read future entries from this post office diary, you can subscribe here: